One of Pythagoras’ many fascinating theories is known as the harmony of the spheres. I remember first hearing this theory mentioned in a lecture almost twenty years ago and being utterly captivated by it. It struck me as such a beautiful idea that I simply had to learn more. The theory is that each heavenly body in the universe emits its own distinct sound as it travels through space. The intervals between the heavenly bodies are said to replicate the intervals between notes on the musical scale, and taken together, these sounds combine to create a celestial and wondrous music:

Pythagoras, employing the terms that are used in music, sometimes names the distance between the Earth and the Moon a tone; from her to Mercury he supposes to be half this space, and about the same from him to Venus. From her to the Sun is a tone and a half; from the Sun to Mars is a tone, the same as from the Earth to the Moon; from him there is half a tone to Jupiter, from Jupiter to Saturn also half a tone, and thence a tone and a half to the zodiac. Hence there are seven tones, which he terms the diapason harmony meaning the whole compass of the notes. [Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, 2.20.]

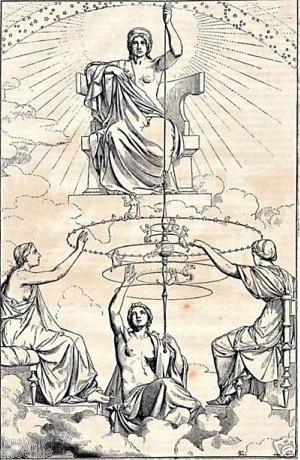

Plato adopts the idea and writes about it in book ten of his Republic. In the myth of Er, Plato describes the journey of a soul after death, the judgement of souls, and the structure of the entire cosmos. At the heart of the cosmos is the spindle of Necessity around which all the orbits of the universe turn. On each orbit, a Siren stands, singing a single note. Together, these eight singing Sirens combine to create a wonderful harmony. Singing along with this music are the three daughters of Necessity, known as the Fates: Lachesis who sings of things that were, Clotho who sings of things that are, and Atropos, the things that are yet to be. [Plato, Republic, 10.616c-617d]

Necessity and the Fates

The idea reappears in the writings of Cicero many centuries later. The universe is described as linked together in nine circles or spheres. The outermost sphere embraces and holds together all the others. As the planets revolve within their spheres, they produce a note, depending on the speed of their revolution. The celestial zone, full of stars, revolves quickly and is said to produce a sharp, high note while the moon is said to produce the lowest tone of all. The combined effect of these sounds is captivating and beautiful:

“What,” I asked, “what is this sound that fills my ears, so loud and sweet?” “This,” he replied, “is that sound, which divided in intervals, unequal, indeed, yet still exactly measured in their fixed proportion, is produced by the impetus and movement of the spheres themselves, and blending sharp tones with grave, therewith makes changing symphonies in unvarying harmony.

Cicero suggests that earthly music can open a pathway back to this celestial harmony:

Now the revolutions of those eight spheres, of which two have the same power, produce seven sounds with well-marked intervals; and this number, generally speaking, is the mystic bond of all things in the universe, And learned men by imitating this with stringed instruments and melodies have opened for themselves the way back to this place, even as other men of noble nature, who have followed godlike aims in their life as men.

The problem for mankind is that, according to Cicero, “the ears of men overpowered by the volume of the sound have grown deaf”. [Cicero, The Dream of Scipio]

This theory of the music of the spheres continued to be influential throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, and reappears in Shakespeare:

Look how the floor of heaven

Is thick inlaid with patens of bright gold.

There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still choiring to the young-eyed cherubins.

Such harmony is in immortal souls,

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.

Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, Act 5, Scene 1.

The harmony of the spheres has clearly inspired poets, mystics, philosophers, musicians and writers for many centuries. Astronomers have even found their own version of the truth, making recordings of the many amazing sounds of space. But can we recapture the inner harmony that Shakespeare suggests we are capable of? For my part, I’m going to close my books for a moment, unplug the headphones, step outside on this late Spring evening and watch the stars. It is time to respond to Cicero’s exhortation: “Come!…how long will your mind be chained to the earth?”

Resources:

BBC Radio 4: In Our Time – The Music of the Spheres:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00c1fct

Sounds of the universe:

Online texts:

Plato’s Republic, 10.614d:

Cicero’s Dream of Scipio:

http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/cicero_dream_of_scipio_02_trans.htm